|

Threads | The St. Louis Tape Paintings

In the mid-1970s, Nickel was experimenting with the materials and techniques of painting — an approach that persisted throughout the St. Louis years. He ordered a 55-gallon drum of Rhoplex, an acrylic medium, and began to make his own paint, optimizing it for spraying. He bought tent-and-awning canvas by the roll and built stretchers to accommodate paintings more than 10 feet wide.

Layers

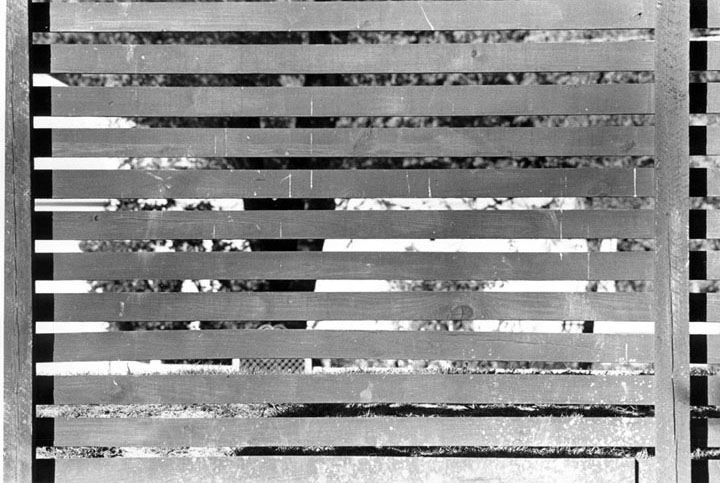

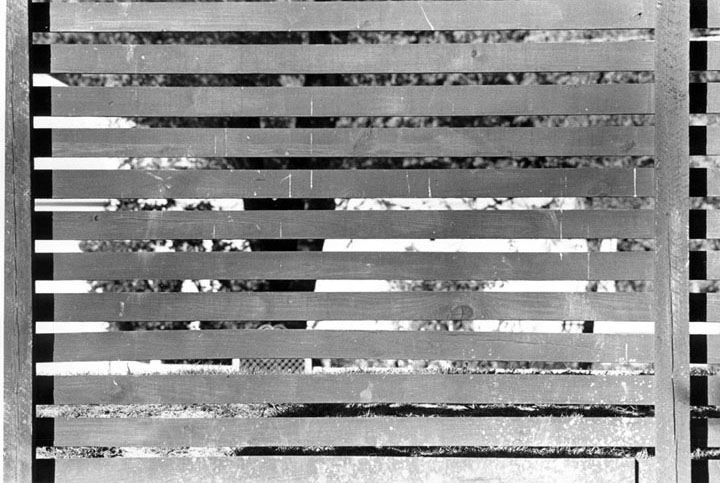

During those St. Louis years, Nickel explored the city and its suburban rings, sometimes hiking along urban railroad tracks, more often pedaling his 10-speed bike, but always with his 35mm camera. He found much that caught his eye, and he studied his photography to understand what had interested him and why. He noticed a common visual theme in several images. Unlike photos that stretched seamlessly from foreground to horizon, these images presented a sequence of layered planes: Venetian blinds or the horizontal slats of a fence in the foreground, perhaps, and visible through the horizontal gaps in the foreground plane, some sort of object, and beyond that object yet another plane.

Tape and strings

Nickel had begun to use templates — initially thousands of masking tape parallelograms the size of postage stamps placed in precise rows directly on the canvas. Above that, he placed a layer of closely spaced parallel strings, stretching them across the canvas on his studio floor and spray-painting the spaces in between. He then removed the strings, peeled off and repositioned the bits of tape, stretched the strings at a different angle, and sprayed again — a tedious, time-consuming iterative process, though at times deeply meditative. By restringing at different angles and spraying different colors, Nickel achieved a surface that appeared almost woven, yet immensely deep. The strings themselves, heavy and fattened almost to a quarter-inch diameter by successive layers of acrylic, began to contribute to that sense of depth by creating lines with ever-softer edges.

These early tape and string paintings date from the early 1970s. The materials and technique continued evolve. The sequence of layers was important — yellow over red over blue yielding a significantly different effect from blue over yellow over red — as were the spray paint opacity and underlying solid color ground.

The large tape paintings

Beginning in 1973, Nickel began adding a foreground of hard-edged opaque lines laid down with a template of masking tape.

Parallel at first, those lines further enhanced the feeling of depth, giving the viewer a sense of gazing into the painting as if through Venetian blinds. By 1974, those foreground lines

began to weave over and under each other in wide bands. Large geometrical

substrates of color began to appear, further amplifying the sensation of layered depth. Nickel produced 18 of these large works at his studio in suburban St. Louis. One of them remains in the permanent collection of the St. Louis Art Museum, purchased by the museum in 1975.

Read about the acquisition in the Bulletin of the St. Louis Art Museum, September/October 1975 (XI:5).

View the 18 large tape paintings.

|